Project Description

Slowly does it

CLIENT: Appelberg Publishing Stockholm

PUBLISHED: SKF Evolution website

ORIGINAL ARTICLE: Slowly does it

CREATED: June 2017

AUTHOR: Fallon Dasey

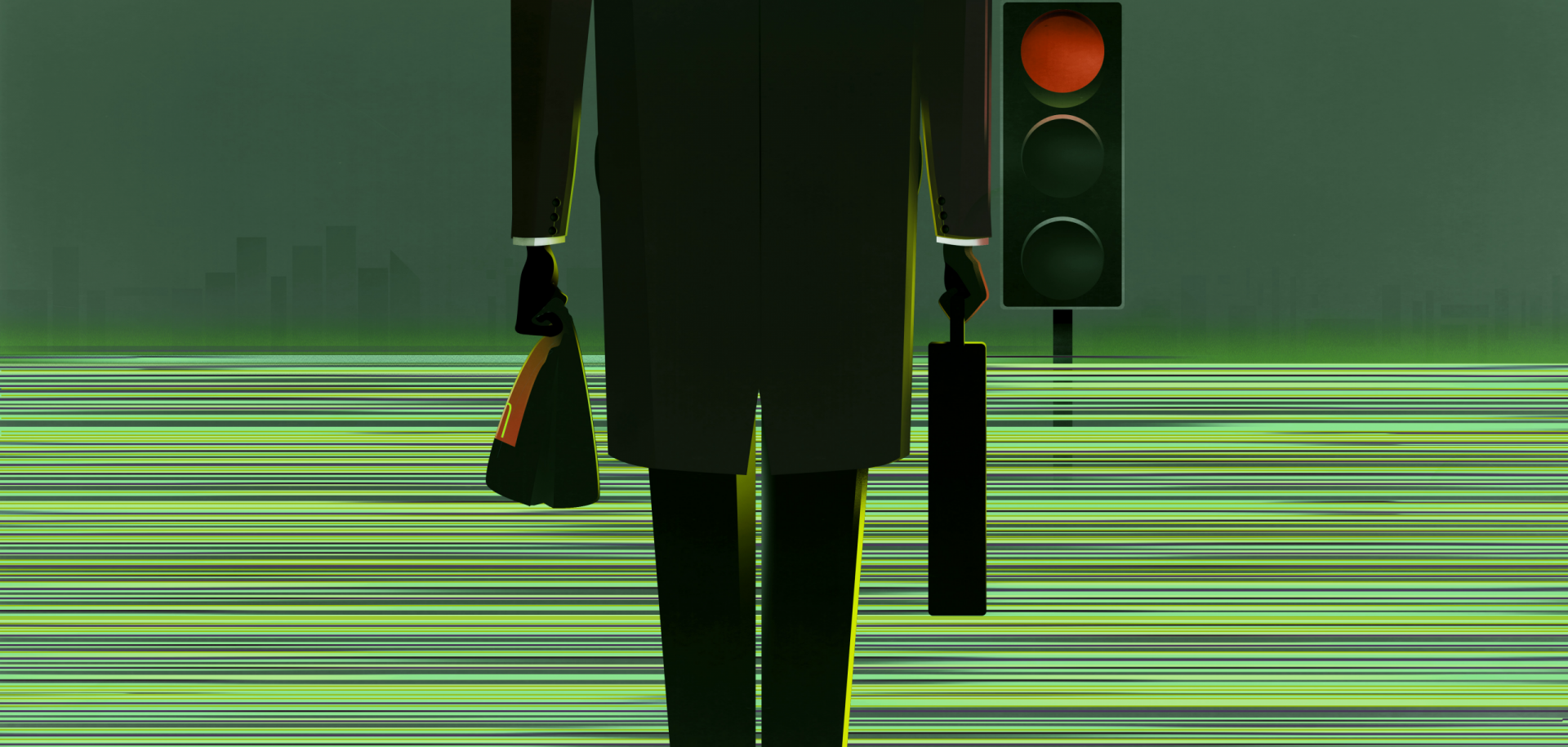

Having taken the culinary world by storm, the “slow movement” is now being embraced by areas ranging from fashion to medicine and manufacturing, with surprising results in terms of productivity.

The pace of life has never been faster. We’re constantly connected to our offices with smartphones; we check our email first thing when we wake up and last thing before we go to bed. Our workdays are busier than ever, often stretching far into the night. We jet across entire continents to attend meetings, striving to do things faster and more efficiently, all the while bombarded by an unending flow of information.

The goal of the slow movement is to encourage people to live, eat and work at a more humane pace, rather than always trying to do things faster and suffering burnout as a possible result.

What if, instead of rushing, we slowed down and savoured life? That’s the philosophy behind the slow movement – a radical re-appraisal of the pace at which human life is conducted. The movement is increasingly winning fans across the world. Rather than always trying to do things faster – and suffering burnout as a possible result – adherents advocate living, eating and working at a more humane pace.

“People are realizing that we are not rats and life is not a race,” says Geir Berthelsen, founder of the World Institute of Slowness and a leading advocate of the slow movement. “We need a whole new mindset, away from the traditional perception of success and status where things like health, relationships and environment are regarded as subordinate.”

Berthelsen, like many others in the slow movement, views the Industrial Revolution as a key turning point in the way humans regard time. The emergence of increasingly sophisticated machines enabled goods to be produced at a previously unimaginable pace. Improved distribution networks helped spawn a corporate culture where the most successful businesses were those that could serve the customer first. Little thought was given to the impact this was having on the quality of human life.

Slow medicine is a concept where doctors try to understand more about patients by spending time with them and listening to them rather than just writing a prescription.

Berthelsen says the origins of the modern slow movement extend back to Italy in the 1980s, when Italian journalist Carlo Petrini led a campaign against the opening of a McDonald’s restaurant near the Spanish Steps in Rome. Petrini questioned exactly why the world needed fast food, later penning a manifesto that urged followers to embrace nutritious, locally sourced food. The idea resonated deeply with food lovers across the planet, and the slow food movement was born.

In the ensuing decades, Berthelsen says, this questioning of the need for speed has spread to a wide range of other disciplines and aspects of life. Cittaslow, for example, is a global organization that aims to create slow towns and cities where life is more pleasant for inhabitants.

“Slow architecture is all about designing cities where maximizing human values is seen as the core focus,” says Berthelsen. “Slow medicine is where doctors try to understand more about patients by spending time with them and listening to them rather than just writing a prescription.”

Berthelsen says that where a slow approach is adopted there are clear and tangible benefits for individuals, including less stress, more time to enjoy life, a greater sense of well-being and fewer incidents of burnout.

The origins of the modern slow movement extend back to Italy in the 1980s, when Italian journalist Carlo Petrini led a campaign against the opening of a McDonald’s restaurant in Rome.

Petrini later penned a manifesto that urged followers to embrace nutritious, locally sourced food. The idea resonated deeply with food lovers all over the world, and the slow food movement was born.

But while individuals might benefit, is going slow bad for productivity and business in general? Not necessarily, says Pierre Moniz Barreto, a French author who studied the impacts of the slow movement on the corporate world to produce the 2015 book Slow Business.

Moniz Barreto says that since around 2000, an increasing number of businesses globally have been reassessing traditional work structures. Some of those who have shortened workweeks and tried to take some of the stress off employees have been rewarded by more efficient and productive workers.

“The slow movement isn’t an apologia for laziness or slowness,” he says. “It’s a question of reason and balance. It’s about time mastery, organization and responsibility.”

Moniz Barreto points to Jason Fried, the co-founder of Basecamp – a highly successful global company selling project management tools – as a prime example of someone who has successfully adopted a slow approach to work. “Fried wrote that when they founded the company, he was working between 10 and 40 hours a week,” says Moniz Barreto. “He believed it wasn’t necessary to do more, and he would say the same thing to his team: ‘When you’re done, you’re done; don’t do extra work. I don’t like workaholics because they do more harm than good.’

“You find it in manufacturing, too,” Moniz Barreto says. “I recently interviewed Anne-Sophie Panseri, the CEO of Maviflex, a large manufacturer of automatic and manual industrial doors, based in Lyon. She has started to introduce some slow techniques and initiatives aimed at stopping overwork that can be applied in a range of industries.”

Moniz Barreto says another great example is American rock climber Yvon Chouinard, who created the Patagonia clothing brand using slow HR policies. The company rejects the notion of fast, disposable fashion, instead offering consumers durable pieces that have been sustainably sourced.

Another advocate of slow fashion is Celine Semaan, founder of the Brooklyn-based Slow Factory, a company that produces silk scarves featuring distinctive images taken by NASA satellites and telescopes. Semaan explains that the company, which she set up four years ago, rejects the approach taken by big clothing chains that produce clothes cheaply with the expectation that they are worn briefly and discarded. Instead, her garments, which are made in Italy, are designed to defy seasonal fashion trends and to be worn for many years.

“With mainstream fashion you have people working in sweatshops for 18 hours a day, seven days a week,” she says. “They’re tired, and their arms cramp. There are so many human rights issues. The clothes produced don’t last for more than a few washes. We wanted to manufacture clothing using artisanship, craftsmanship and traditional techniques that make garments last.”

So what lies ahead? Given the ground that the slow movement has made in recent years, Geir Berthelsen is confident it will become more widely accepted. “There’s no doubt that it’s getting bigger and bigger,” he says. “I think it’s just going to continue to grow until we get balance in our lives.”

Websites:

www.theworldinstituteofslowness.com

www.pierremonizbarreto.wixsite.com/slowbusiness